The P.E.I. Railway was started by the Island government in 1871, but the debt-riddled construction was taken over by the Dominion government in 1873 as part of the colony's entry into Confederation. The main line was complete by 1875, and the building of a branch line stretching from Souris to Tignish-- the two communities at located on opposite tips of our crescent-shaped Island-- was begun in 1872. By 1880, there were two trains running daily across the province, one eastbound and the other westbound. But the completion of these lines did not mark the end of railway-building on the Island, as changes to transportation systems made the process of tearing up rails and laying down new ones into a seemingly never-ending one. In 1885, the line was up and running between Emerald Junction and Cape Traverse, the port from which the steam ferries sailed out across the Northumberland Strait. But this route was abandoned soon after new ice-breaking ferries were introduced at Borden in 1917, as these boats were capable of taking on railway cars and transporting them to the mainland. Unfortunately, this development was not one which the original railway contractors had foreseen, and the Island paid dearly for the oversight.

The

problem was that the P.E.I. Railway had been built with

narrow gauge rails (3' 6") instead of the standard

gauge (4' 8"), as the smaller rail system was

cheaper and the Island was a self-contained line which--

at the time-- only had to be concerned with its own

standards. But the cost-cutting measure ended up costing

far more than it ever saved. If the Island wanted to take

advantage of the new ferries, they would have to use cars

which ran on the same standard gauge as the mainland. And

if they wanted to get these cars to Borden, they would

have to lay down a new set of 4' 8" rails on the

Island. Between this narrow-gauge incompatibility, and

the massive cost overruns of the original construction,

the P.E.I. Railway did not quite live up to its advance

billing as an economic boon.

The

problem was that the P.E.I. Railway had been built with

narrow gauge rails (3' 6") instead of the standard

gauge (4' 8"), as the smaller rail system was

cheaper and the Island was a self-contained line which--

at the time-- only had to be concerned with its own

standards. But the cost-cutting measure ended up costing

far more than it ever saved. If the Island wanted to take

advantage of the new ferries, they would have to use cars

which ran on the same standard gauge as the mainland. And

if they wanted to get these cars to Borden, they would

have to lay down a new set of 4' 8" rails on the

Island. Between this narrow-gauge incompatibility, and

the massive cost overruns of the original construction,

the P.E.I. Railway did not quite live up to its advance

billing as an economic boon.

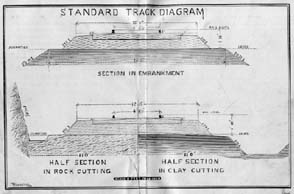

Even so, the building of this railway system was a massive feat of engineering, which required the hard work and sweat of hundreds of Islanders. Five main components were used in the construction of the tracks themselves: rails, ties, spikes, ballasts, and subgrade. The rails consisted of the steel lengths bolted or welded together to form the running surface for the train. The subgrade was the solid ground used as a base, which was then covered by the ballast, the large amount of rock material that comprised the actual rail bed. Millions and millions of tons of mainland gravel had to be shipped across the Northumberland Strait to serve as the ballast, as Island sandstone was too fragile to fit the bill. The ties were almost always wood, but were also sometimes made of concrete. The rails were fastened to the tie with spikes, which provided the proper gauge and also helped distribute the stress properly on the ballast layer.

P.E.I.'s weak bedrock-- the red sandstone-- made maintaining the rail lines a constant battle, as the tracks were not resting upon the most solid of foundations. When the spring thaw arrived and the frost heaves left the ground, the tracks would become an Island-wide obstacle course of buckles and dips, which proved highly problematic for trains designed to travel over level surfaces. The process of fixing the tracks was every bit as intensive as the modern-day ritual of filling potholes on the roads, and just as continuous.

One important position

with regard to railway maintenance was that of the track

master, who made monthly inspections of the section--

riding on a hand-car or from the back of a train-- and

would submit written reports on its condition. However,

the day-to-day upkeep of the line fell to the track

foreman and workers, who were the front-line people

responsible for the safe passage of trains. The foreman

would walk over his section every morning and inspect it

closely, and he would take many tools and parts along

with him, as missing bolts, loose nuts, and broken spikes

had to be remedied immediately. Oftentimes, the

unpredictable rail beds required quite a bit of

improvisation and quick thinking on his part. Shims were

placed under rails which had started to dip; his book of

regulations stated that "in no case are Shims

thicker than three inches to be used". This rule

book also stated that, when an animal was fatally wounded

by the train, he was to end its suffering and have it

removed post haste.

One important position

with regard to railway maintenance was that of the track

master, who made monthly inspections of the section--

riding on a hand-car or from the back of a train-- and

would submit written reports on its condition. However,

the day-to-day upkeep of the line fell to the track

foreman and workers, who were the front-line people

responsible for the safe passage of trains. The foreman

would walk over his section every morning and inspect it

closely, and he would take many tools and parts along

with him, as missing bolts, loose nuts, and broken spikes

had to be remedied immediately. Oftentimes, the

unpredictable rail beds required quite a bit of

improvisation and quick thinking on his part. Shims were

placed under rails which had started to dip; his book of

regulations stated that "in no case are Shims

thicker than three inches to be used". This rule

book also stated that, when an animal was fatally wounded

by the train, he was to end its suffering and have it

removed post haste.

When

the trackman discovered these types of hazards, he would

use a system of red, green, and white signals to alert

train personnel and-- most importantly-- oncoming trains.

Red meant danger ahead; green indicated caution, proceed

slowly; and white meant that all was right, go on. The

signals were made with flags in the daytime, and at

night, with lanterns or even torpedoes. The rules

explicitly barred track foremen from wearing red on the

job, as even a glimpse of that color would set a train on

high alert. In the winter, these trackmen waged a battle

against the accumulation

of snow on the rails, and advised

the trackmaster continually about its depth, even on

Sundays. Teams of snow shovellers were hired to clear the

massive drifts, and tragically, these men were

occasionally killed by unexpected trains. The engines

could not see around their plows, and the snow cuttings

were sometimes too high for the men to climb out on time.

When

the trackman discovered these types of hazards, he would

use a system of red, green, and white signals to alert

train personnel and-- most importantly-- oncoming trains.

Red meant danger ahead; green indicated caution, proceed

slowly; and white meant that all was right, go on. The

signals were made with flags in the daytime, and at

night, with lanterns or even torpedoes. The rules

explicitly barred track foremen from wearing red on the

job, as even a glimpse of that color would set a train on

high alert. In the winter, these trackmen waged a battle

against the accumulation

of snow on the rails, and advised

the trackmaster continually about its depth, even on

Sundays. Teams of snow shovellers were hired to clear the

massive drifts, and tragically, these men were

occasionally killed by unexpected trains. The engines

could not see around their plows, and the snow cuttings

were sometimes too high for the men to climb out on time.

As the years passed, the tracks were travelled

less and less frequently on the Island, and on December

31, 1989, the last part of the railway was abandoned by

CN Rail. Slowly but surely, the once-proud rail system

began to be ripped up and sold for scrap. However, the

extensive system of rail beds was built to last, and

plans have been assembled to put it to good use. The

abandoned rail lines  are being converted

into a section of the nation-wide Confederation Trail, a

network of hiking, biking, and snowmobiling trails that--

when completed-- will stretch from coast to coast. Today,

the former railway line between Kensington and Summerside

not only promotes the health and well-being of the

community, but also represents one part of an important

project for knitting the country together, as the railway

did for so long.

are being converted

into a section of the nation-wide Confederation Trail, a

network of hiking, biking, and snowmobiling trails that--

when completed-- will stretch from coast to coast. Today,

the former railway line between Kensington and Summerside

not only promotes the health and well-being of the

community, but also represents one part of an important

project for knitting the country together, as the railway

did for so long.