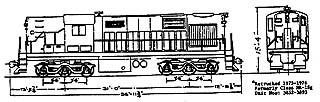

By 1947, the change from steam to diesel powered locomotives on Prince Edward Island was well underway. Instead of the steam which had previously driven the motor, the new diesel electric locomotive featured a gas engine, which powered an electric generator. The apparent advantages of the diesel engine over its steam-powered forerunner were overwhelming, and the change was made in the name of progress and cost-cutting.

Diesel

engines were more economical to operate, with higher fuel

efficiency, lower maintenance, and fewer breakdowns.

Unlike steam engines, the new gas-powered model did not

need to be serviced or changed every 200 miles. They were

also more powerful than steam engines and allowed one

engineer to handle extra freight cars, making for a more

streamlined and efficient rail system. It also permitted

the railway companies to eliminate some jobs, as the

position of fireman-- the crew member who stoked the fires

to produce steam-- was made obsolete by the new engines.

With all of these factors working in its favor, the

replacement of steam by diesel was quick and total. In

1950, 91 percent of the trains in Canada were steam

powered; within a decade, that number had dropped to just

over 1 percent.

Diesel

engines were more economical to operate, with higher fuel

efficiency, lower maintenance, and fewer breakdowns.

Unlike steam engines, the new gas-powered model did not

need to be serviced or changed every 200 miles. They were

also more powerful than steam engines and allowed one

engineer to handle extra freight cars, making for a more

streamlined and efficient rail system. It also permitted

the railway companies to eliminate some jobs, as the

position of fireman-- the crew member who stoked the fires

to produce steam-- was made obsolete by the new engines.

With all of these factors working in its favor, the

replacement of steam by diesel was quick and total. In

1950, 91 percent of the trains in Canada were steam

powered; within a decade, that number had dropped to just

over 1 percent.

The last of the steam engines

was retired on P.E.I. in 1950. Partly because it had a

small, self-contained rail system, the Island had been at

the forefront of the move from steam to diesel, first

serving as a testing ground  for

the new gas-powered engines and then becoming the first

province in Canada to complete the switch-over. At first,

Island railwaymen appreciated how the diesel engines

eliminated many of the back-breaking tasks that their job

had involved, such as the never-ending chore of shoveling

coal. But while the steam engines may have required

constant service, engineers were most often able to patch

up their own engines and make it back to the station for

repairs. Diesel engines, on the other hand, were far more

complex. When breakdowns occurred in a diesel engine,

they were usually electrical in nature, and another

diesel engine would have to be called to tow it back to

the repair yard.

for

the new gas-powered engines and then becoming the first

province in Canada to complete the switch-over. At first,

Island railwaymen appreciated how the diesel engines

eliminated many of the back-breaking tasks that their job

had involved, such as the never-ending chore of shoveling

coal. But while the steam engines may have required

constant service, engineers were most often able to patch

up their own engines and make it back to the station for

repairs. Diesel engines, on the other hand, were far more

complex. When breakdowns occurred in a diesel engine,

they were usually electrical in nature, and another

diesel engine would have to be called to tow it back to

the repair yard.

Increasingly, the train crews seemed indifferent toward-- or even critical of-- the diesel, a far cry from the pride that they remembered having for their steam engines. In the steam engine, there would always be a tool kit in the cab, ensuring that whatever possible stop-gap measures were taken to get the train to the station. When one Island engineer-- newly placed on a diesel engine-- was asked what type of tool kit he carried, he disgustedly pulled out a piece of scrap paper with the name and telephone number of a diesel foreman from Moncton. Also, some railwaymen found that the modernization of trains had left the trains without personality. There was a definite romance surrounding the steam engine, which roared into the station like a dragon before coming to a stop with its trademark hiss. The comparatively silent, electrically-powered diesel engines may have brought efficiency to the railway, but deprived it of a good measure of its mystique. Railroaders looked on the steam engine as an animate, living and breathing object-- always referring to the engine as "she"-- and these fundamental changes to their way of life did not come easily.

However, any debate about the advantages

of steam or diesel soon was immaterial, as it became

increasingly clear that the entire railway was in real

danger of disappearing from P.E.I. It became rarer and

rarer sight to see even a modern diesel engine rolling

down the Island tracks. As soon as everyone owned an

automobile, they no longer wanted to cope with railway

schedules, and on October 25, 1969, the trains picked up

Island passengers for the last time. Those who wanted to

catch a train had to be bussed to Moncton. Also, farmers

began relying on trucking instead of trains to get their

harvests to market, and the Trans-Canada Highway eclipsed

the CNR as the main shipping route. The closing of

stations, which began in 1962, progressed until there

were only stations in major centres like Summerside and

Charlottetown, and even these only had a corporal's guard

on staff.

However, any debate about the advantages

of steam or diesel soon was immaterial, as it became

increasingly clear that the entire railway was in real

danger of disappearing from P.E.I. It became rarer and

rarer sight to see even a modern diesel engine rolling

down the Island tracks. As soon as everyone owned an

automobile, they no longer wanted to cope with railway

schedules, and on October 25, 1969, the trains picked up

Island passengers for the last time. Those who wanted to

catch a train had to be bussed to Moncton. Also, farmers

began relying on trucking instead of trains to get their

harvests to market, and the Trans-Canada Highway eclipsed

the CNR as the main shipping route. The closing of

stations, which began in 1962, progressed until there

were only stations in major centres like Summerside and

Charlottetown, and even these only had a corporal's guard

on staff.

The last train into Kensington passed

through on December 22, 1989. In an interesting footnote

to history, the train was traveling in reverse on its way

through town, backing up all the way to New Annan to pick

up a tank car. In many ways, this backwards journey out

of town was an appropriate symbol for how the railway

disappeared from the Island, in a slow, drawn-out retreat

from its former status as a vital transportation system.

The last train left aboard the ferry on December 31,

1989, over 114 years after the first scheduled train

traveled over the P.E.I. Railway. Its long whistle, part of the fabric

of Island life, will never be heard again.

The last train into Kensington passed

through on December 22, 1989. In an interesting footnote

to history, the train was traveling in reverse on its way

through town, backing up all the way to New Annan to pick

up a tank car. In many ways, this backwards journey out

of town was an appropriate symbol for how the railway

disappeared from the Island, in a slow, drawn-out retreat

from its former status as a vital transportation system.

The last train left aboard the ferry on December 31,

1989, over 114 years after the first scheduled train

traveled over the P.E.I. Railway. Its long whistle, part of the fabric

of Island life, will never be heard again.