For the early

settlers, the blacksmith was perhaps the most essential

tradesman. Not only did he make the iron parts for the

first farming implements, he also could repair all iron

objects by hammering them by hand on an anvil. After

heating the iron until white-hot, the blacksmith would

then shape and wield a multitude of objects from it,

including carriage bolts and wheels, iron work for fishing

craft, cooking utensils, and most importantly,

horseshoes.

For the early

settlers, the blacksmith was perhaps the most essential

tradesman. Not only did he make the iron parts for the

first farming implements, he also could repair all iron

objects by hammering them by hand on an anvil. After

heating the iron until white-hot, the blacksmith would

then shape and wield a multitude of objects from it,

including carriage bolts and wheels, iron work for fishing

craft, cooking utensils, and most importantly,

horseshoes.

Blacksmiths who made horseshoes were called farriers, derived from the Latin word for iron. At a time when horses were the only means of transport, the blacksmith was important to not only individual farmers and travelers, but also to merchants whose businesses depended on transporting their goods to other places. Also, because they spent much of their time shoeing horses, blacksmiths gained a considerable amount of knowledge about equine diseases. The blacksmith doubled as a veterinarian, treating and preventing the hoof-related ailments that could hobble a valuable animal.

In Kensington and area, blacksmiths were particularly busy during the winter months. One common winter task was mussel mud digging, where the horses would haul organic material up from river bottoms through the ice. Horses had to be well shod to get the necessary foothold on the ice. In Clinton, the local blacksmith was able to shoe over twenty horses a day. Even so, he would not want to hurry too much, because a slip of a nail might result in an upset horse and a backwards kick with his name on it!

In the early 1900's, the average price for fitting a horse with new shoes was 80 cents, parts and labour included. If the blacksmith was asked to take off the old shoes, caulk the hooves, and then place the old shoes back-- somewhat like a past equivalent of rotating tires-- the blacksmith would charge approximately 40 cents. While it might not have been posted, there was an unspoken understanding about the going rate for almost every blacksmithing task, from making anchors to oyster rakes. Alex Nicholson, a blacksmith from Clinton in the early 1900's, charged 20 cents to sharpen a coulter (or turf-cutter) on farm machinery. Having your pot repaired would set you back 20 cents, and getting your buggy running smoothly again usually ran in the vicinity of 65 cents.

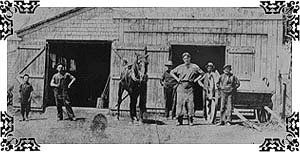

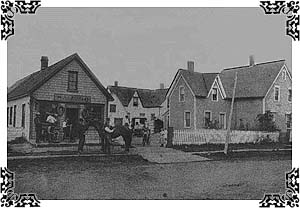

Herbert Moase

(1865-1942) began his career as a blacksmith in

Kensington, and sold his operation to Tyndall and Fred

Semple in 1918. Tyndall Semple had started out as a

blacksmith in Traveller's Rest, P.E. I., which is

approximately 5 miles west of Kensington. The Semple

family is a classic example of how the blacksmith's work

translated into expertise in dealing with horses. Tyndall Semple

became one of the most respected horsemen in the Maritime

harness-racing

circuit, involved in the training, breeding, and driving

some of its great champions. He continued to race

actively until he was eighty-six.

Herbert Moase

(1865-1942) began his career as a blacksmith in

Kensington, and sold his operation to Tyndall and Fred

Semple in 1918. Tyndall Semple had started out as a

blacksmith in Traveller's Rest, P.E. I., which is

approximately 5 miles west of Kensington. The Semple

family is a classic example of how the blacksmith's work

translated into expertise in dealing with horses. Tyndall Semple

became one of the most respected horsemen in the Maritime

harness-racing

circuit, involved in the training, breeding, and driving

some of its great champions. He continued to race

actively until he was eighty-six.

Many apprentices came to Kensington to serve under its blacksmiths, learning the art of shaping metal from veterans of the trade. The 1890 Island Directory lists Archibald Delaney as a blacksmith located in French River, P. E. I., approximately 10 miles northeast of Kensington. His son, Emmerson, went on to train at the Semple smithy in Kensington, and then returned to French River and established his own business. Working full-time until the age of eighty, he only retired from his forge and anvil in the 1960's, when there were few horses left to be shod.

Although the blacksmith was at one point considered an indispensable part of the community, the need for his services declined when the horse was replaced by the automobile, and machine forging made human hands obsolete. Composed by local poet Bessie Wheeler, this poem evokes the bygone era of the blacksmith, when the clang of the hammer on the anvil was the heartbeat of every village.

The Blacksmith Shop

The blacksmith shop stands by

the side of the road,

Where it's stood most a

century before,

But its doors are closed

and its roof is sagged.

And the anvil will ring

no more.

The horses that came for bright

new shoes

Left their footprints on

the floor;

But they are gone and

will never return,

So the anvil need ring no

more.

The faithful smith and the

faithful horse,

Have passed with an era

before,

And have paved the way

for a different day

When the anvil will ring

no more.

Memories are all that are left,

With those who watch at

its door;

These, too, shall toil

then pass away

And the anvil will ring

no more.

Shoemaker | Tailor and Dressmaker | Livery Stable | Herbert R. Moase, Tradesman