The

profession of the farmer was not so much a single job,

but a combination of vocations. To keep his farm up and

running, the farmer had to be ready to wear any number of

different hats, so to speak. He was a botanist with his

crops, a veterinarian with his livestock, and a

businessman when negotiating the best price for his

yield. He even had to play the role of weatherman, doing

the hay while it was dry and taking in the potatoes

while the soil was still damp. Farmers may not have

received much formal education but-- by any standard--

they possessed a wealth of knowledge, picked up from past

generations and from each other.

The

profession of the farmer was not so much a single job,

but a combination of vocations. To keep his farm up and

running, the farmer had to be ready to wear any number of

different hats, so to speak. He was a botanist with his

crops, a veterinarian with his livestock, and a

businessman when negotiating the best price for his

yield. He even had to play the role of weatherman, doing

the hay while it was dry and taking in the potatoes

while the soil was still damp. Farmers may not have

received much formal education but-- by any standard--

they possessed a wealth of knowledge, picked up from past

generations and from each other.

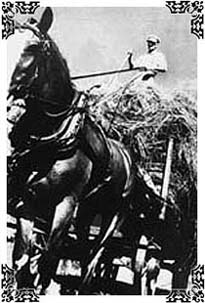

The sharing of ideas, equipment, and manpower was an essential part of traditional farm practice. When there were large tasks to be accomplished, neighbors always seemed to be ready with a helping hand. These collective efforts, especially important during cropping and harvesting seasons, were known as 'frolics.' Farmers would organize a group of men to help with the harvesting of hay, or to raise the frame and rafters of a new building. The reward for putting in a hard day's work would be a large meal, prepared by the women, followed by a night of fiddle music, dancing, and festivity.

One of the most

important sources of information for the early farmer was

the moon, which served him at different times as a

makeshift calendar, weather report, or even good luck

charm. The phases of the moon were used as a planting

guide, partly on the basis of reasoned experience and

partly out of superstition. Potatoes were planted in the

dark phase of the moon in May, while cucumber and

pumpkins were not to be put in the ground until the dark

phase of the moon in June. These rules-of-thumb had a

good reason behind them: the Island is prone to heavy

frosts until the end of May, which could wipe out above

ground crops.

But

other moon-related superstitions had less immediately

discernible reasons behind them. Pigs, for instance, were

supposed to be slaughtered during a moonless night to

prevent the meat from shriveling. When the moon was on

the wane, it was said, splitting firewood was easier and

the bark would peel right off the 'longers,' or fence

posts. Potato sets-- the sectioned potatoes used as

seed-- were to be cut before a full moon and dried in the

sun. Traditions die hard, and many older Island farmers

still swear by these beliefs.

Farmers also needed to keep a watchful eye trained on the health of their livestock. With veterinarians few and far between, they had to rely on their own diagnoses and apply traditional remedies, often passed down through several generations. Colic in horses was treated by 'drenching' the animal-- administering a purgative made from birch tree bark-- and then walking it until the medicine brought relief. Cows who had overfed on green grain or clover would have to be stabbed in the stomach, with aprecise incision that relieved the painful buildup of gas.

Until

recently, the Island farm was a mainly self-sufficient

operation, and there was little need or occasion to

record its financial dealings. One local farmer

remembered how his father kept a tally of farm production

with notches on his barn door. When the barn caved in,

all the records went along with it. But the lack of

written records did not mean that the farm itself was

ready to fall apart at any minute. The farmer carried his

calculations around in his head, always knowing how much

a field or an animal should produce. However, the rise of

large, commercial farms has required that farmers develop

a more formal managerial style, with cost and revenue

tabulations and payroll accounts. To be successful, the

modern farmer has to fulfil another role over and above

the many that his predecessors perfomed: the role of a

businessman.