Crop Rotation | Cultivation | Weed and Insect Control | Harvesting

![]()

Farmers have almost always practiced some form of crop

rotation, varying what is planted in a field from year to

year to preserve the soil. A crop like the potato

absorbs more nutrients from the ground than certain other

crops, such as hay

or grain. To prevent the land from

becoming depleted, the farmer rotates the crop he plants

in each of his fields, making certain that the demanding

ones are not grown on the same parcel of land for several

years running. Besides conserving soil nutrients, crop

rotation is an effective means of combating weeds.

When farmers adhered to mixed farming

practices, they used a longer crop cycle known as the

'seven-year rotation'-- a cycle which, despite its name,

could last anywhere from four to eight years. Under this

rotation, a year of potatoes would be  followed

by a year of grain, a clover crop, and then two years as

hay. The field would then be put out to pasture for

another one or two more seasons, and finally a root

crop-- such as potatoes or turnips--

would be planted in the field again. There was an

unwritten, widely respected rule that potatoes were not

to be cultivated in the same field two years in a row.

followed

by a year of grain, a clover crop, and then two years as

hay. The field would then be put out to pasture for

another one or two more seasons, and finally a root

crop-- such as potatoes or turnips--

would be planted in the field again. There was an

unwritten, widely respected rule that potatoes were not

to be cultivated in the same field two years in a row.

However, as farms expanded in the twentieth

century, crop rotations became more and more attenuated.

While mixed farmers had another immediate use for the

land where they grew potatoes last season, it is more

difficult to convince farmers who specialize solely in

potatoes to leave a field fallow for several years

between plantings, especially when they have large

commercial contracts to meet. Nevertheless, most

commercial farmers do not discount the wisdom of the

past, and maintain some system of crop rotation in the

best interests of their land.

![]()

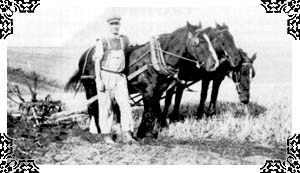

Believing that deep cultivation would ruin the land,

traditional farmers paid close attention to the depth at

which they were breaking the soil. Perhaps they need not

have worried as much as they did; the spring-tooth

harrows they used were light and only dug into the ground

four to five inches. Since the ground was not loosened

very deeply, the farmer could cultivate more often,

ensuring that the land remained soft and able to retain

moisture.

![]()

The farmer had a whole raft of

different strategies for keeping weeds out of his

well-tended fields. Early spring cultivation and early

fall plowing exposed weed seedlings to sunlight and

killed a significant portion of them. On other occasions,

weeds were simply physically removed, perhaps the only

surefire method of preventing their spread. The problem

of couch grass was combated by plowing buckwheat over the

affected field. Today, weeds are causing more

difficulties than they ever have before, and many blame

this problem on the increased use of fertilizers and soil

degradation.

For early farmers, insect control was none too

complicated. For instance, to rid their gardens of

earwigs, they tried dousing them with dishwater. The

Colorado Potato Beetle was undoubtedly the greatest

insect threat for potato farmers. The first pesticide

used to battle this beetle was called Paris Green,  and

farmers had to shake it on the leaves of their potato

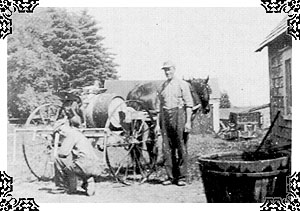

plants manually. Later, there appeared on the market a sprayer

which consisted of a wooden cask on wheels, where the

spraying pump was driven by a bicycle-style chain

attached to the axle. The contraption sprayed faster or

slower, depending on how fast the horses were pulling it

or whether the field went downhill. Before potatoes are

harvested, the potato plant must be killed; most farmers

today use herbicides to assist in killing the tops. In

the past, some farmers did not bother with killing the

tops themselves, waiting instead for the heavy fall

frosts to eventually do the job for them. But when DDT

was introduced after World War II, the widespread use of

chemicals quickly replaced traditional means of weed and

insect control.

and

farmers had to shake it on the leaves of their potato

plants manually. Later, there appeared on the market a sprayer

which consisted of a wooden cask on wheels, where the

spraying pump was driven by a bicycle-style chain

attached to the axle. The contraption sprayed faster or

slower, depending on how fast the horses were pulling it

or whether the field went downhill. Before potatoes are

harvested, the potato plant must be killed; most farmers

today use herbicides to assist in killing the tops. In

the past, some farmers did not bother with killing the

tops themselves, waiting instead for the heavy fall

frosts to eventually do the job for them. But when DDT

was introduced after World War II, the widespread use of

chemicals quickly replaced traditional means of weed and

insect control.

![]()

Early farmers

cut their fields of grain using scythes

and sickles. But the real job did not even begin until

after the grain was cut. The most difficult task was

'threshing,' or separating the kernels of wheat from the

chaff. At first, the grain would be threshed using

hand-held flails, beaten on the wooden floor until all

the wheat had fallen from the stalk. Later, a horse-driven

machine was adopted, where a team

rode on a treadmill to drive the threshing action. Early

potato harvesting was done by hand, filling baskets that

were left along the side of a row and picked up by a

horse and cart. These methods of harvesting were

extremely labour intensive; when potato diggers

and combines

arrived on the scene, few objections were heard from

weary farm families.

Early farmers

cut their fields of grain using scythes

and sickles. But the real job did not even begin until

after the grain was cut. The most difficult task was

'threshing,' or separating the kernels of wheat from the

chaff. At first, the grain would be threshed using

hand-held flails, beaten on the wooden floor until all

the wheat had fallen from the stalk. Later, a horse-driven

machine was adopted, where a team

rode on a treadmill to drive the threshing action. Early

potato harvesting was done by hand, filling baskets that

were left along the side of a row and picked up by a

horse and cart. These methods of harvesting were

extremely labour intensive; when potato diggers

and combines

arrived on the scene, few objections were heard from

weary farm families.