It

is no exaggeration to say that-- without the railway--

there would be no town of Kensington at all, at least in

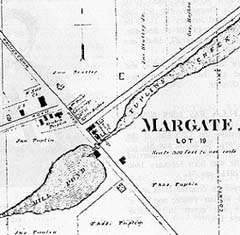

the shape we know it today. In the 1860s, most business

was transacted via water routes, and as a land-locked

community, Kensington was cut off from the prosperity

which came from sea-going trade and the thriving ship-building

industry. The commercial centres in

the region were those with good ocean frontage, such as

Margate, Malpeque, and Cascumpec (map).

From Margate, for instance, Reuben

Tuplin

oversaw a mercantile business which traded with locales

as far-flung as England and the Caribbean, as well as a

shipyard that constructed the holds in which his goods

were shipped. The thriving village also boasted grist and

lumber mills, several smithys, and a carriage factory.

Tuplin

oversaw a mercantile business which traded with locales

as far-flung as England and the Caribbean, as well as a

shipyard that constructed the holds in which his goods

were shipped. The thriving village also boasted grist and

lumber mills, several smithys, and a carriage factory.

Kensington, in comparison, was a bit of a one-horse town. As Orville Darrach-- a descendant of the Tuplin's-- recalled several decades later, "There was no Kensington! There was nothing there but a tavern and a coach-house ... you couldn't get a cart through it!" While the town paths were certainly passable, his assessment is on the whole an accurate one. The main reason for the first settlement in Kensington was that the place represented the convergence of five main roads. But its first name, Five Lanes End, could also have served as a description of what was located there-- the end of five bridle paths, surrounded by woods. When settlers began arriving between 1820 and 1840, such as Thomas Barrett and Thomas Sims, they built public houses and liveries to serve travellers on the Old Post Road. But there was still little reason for the re-named village of Barrett's Cross to expand beyond these humble beginnings. The roads which met in the village were of very poor quality, and most people travelling from Summerside to Charlottetown chose to go by boat, rather than submitting themselves to the dust and slowness of land travel. In 1862, the name of the town was changed to the more regal-sounding Kensington, after the birthplace of Queen Victoria, but its fortunes stayed much the same. The reasons were simple: no access to the water, no access to trade.

But an event occurred in 1871 which would

drastically alter the town's future: the plans to build

the P.E.I. railway. That year, the Hon. J.C. Pope

passed legislation for the building of a railroad that

would run the entire length of the Island, a measure designed

to improve the colony's poor system of overland

transportation. The coming of the railway promised major

changes to the way in which business

was conducted on the Island. Instead of always having to

be carted to port, exports could now be picked up all

along the inland rail line, and merchants could receive

their imported dry goods even if they were not located

next to the water. Although he expressed some doubts that

Island could support its own railway, Reuben Tuplin

envisioned an era of even more prosperity for Margate.

Anticipating this new growth, he drew up plans for a

luxurious hotel and diningroom, and even toyed with the

idea of starting up his own bank to manage all the

financial windfalls.

But Tuplin was in for the surprise of his

life. When the railway route through the district was

finally announced, it completely bypassed Margate and

went through Kensington instead, the little place where a

cart could  barely

pass. With this one decision, the fortunes of the two

towns were instantly reversed: now Kensington was

destined to become the commercial centre for the

district, and the once-prosperous Margate would almost

certainly decline in importance.

barely

pass. With this one decision, the fortunes of the two

towns were instantly reversed: now Kensington was

destined to become the commercial centre for the

district, and the once-prosperous Margate would almost

certainly decline in importance.

Why was Kensington chosen over Margate? Like many other surprising decisions made by Island governments before and since, the choice reeked strongly of political interference. The contract which the colonial government had signed with the Schrieber and Burpee railway company specified no exact details on the route, and the immediate result of this oversight was a process of influence-peddling, bribery, and general corruption unlike any the Island had ever seen. Politicians and merchants were willing to fork out huge kickbacks-- into the thousands of dollars-- to ensure that the tracks passed through their town or next to their business.

The Charlottetown Patriot of September 28, 1871 was none too circumspect in its report on how the curve into Kensington was decided upon. It tells of a private meeting held in Summerside between the government leaders, including W. C. Pope himself; representatives from Kensington named McDonald and Strong; and the railway contractors, Burpee and Schrieber. While the "ostensible subject of the meeting was to consult the contractors respecting the location of the line," the Patriot ventures its guess that the real purpose was to buy the votes of McDonald and Strong on the overall railway route. The price they demanded for their support, of course, was the assurance that a station be built in Kensington.

These unexpected alterations did not go unnoticed. The Islander of October 20, 1871 records that "the malcontents are making a great fuss over the route which has been settled upon for the railroad," and that they were "especially loud ... in their denunciation of the government for having sanctioned the running through Kensington." Among those upset about the decision were a gaggle of land speculators, who had bought tracts of land in Margate and Malpeque as sure bets for railway access. Less self-interested objectors pointed out that the route through Kensington was more than three miles longer than the planned course through the Dunk River Valley, an additional distance which would cost the tax-payer tens of thousands more. Another feature of the route which was widely decried was the way in which it crisscrossed the countryside, instead of following a cheaper, as-the-crow-flies path. With everyone lobbying to have the tracks go by their doorstep, the line acquired bends and curves until such point that-- as was recorded February 21, 1872 in the Patriot-- the rails "crosse[d] the main post road four times in three miles in the same locality."

But by 1875, the passing of the rails through Kensington was a done deal, and area residents could do little else but accept the consequences. In Margate, Reuben and Harriet Tuplin recognized that their decision had been spelled out for them by the railway contractors. If they wanted to remain successful, there was nothing they could do but follow the rail lines and move to Kensington. Tuplin knew that he had to buy land while the price was still low, and after making a transaction with Thomas Sims, built an even larger store near the bustling railway station. Over the following years, other merchants and tradesmen soon began following his lead. This influx of people and money quickly made a boom-town out of Kensington, and left the once-thriving Margate as a ghost of its former self. Thanks to the railway, and a few back-room deals in Kensington's favor, Margate is now famous for its beautiful rolling hills, not its business district.